Maite de Orbe: A moment opposite to blindness

What if a photo could tell the truth better than your memory? We talked intimacy, obsession, and what’s left behind.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you walk us through the development of “A moment opposite to blindness” which was on view at Miłość Gallery? It brings together work from so many places, Chile, The Gambia, the UK, and more. What pulled you to each location? Did they shape the kind of images you were making?

The building of “A moment opposite to blindness” actually came with the opportunity to do a solo show. It wasn’t a project I had been shooting with anything in mind. I’ve always worked in a documentary way, across different projects, and when I was offered this, I didn’t feel like I wanted to focus on just one of them. Instead, I saw it as a chance to step back and ask myself: What is it that I’m really searching for when I make images? What connects the work across all these experiences? So rather than selecting a single body of work, I started to think about the images that have stuck with me. What are the images that over time have stuck that I’ve felt seen or represented by?

In terms of geography, I don’t think the locations are what matter most. The question is, How do we find ourselves wherever we go? Many of these images were made while I was traveling for work. I’d finish for the day, and then spend the evening walking and observing. I would ask myself, What is it about this place that I see myself in? So I think in that sense, it's been a bit more of an exercise of understanding. How is it that we find belonging wherever we go?

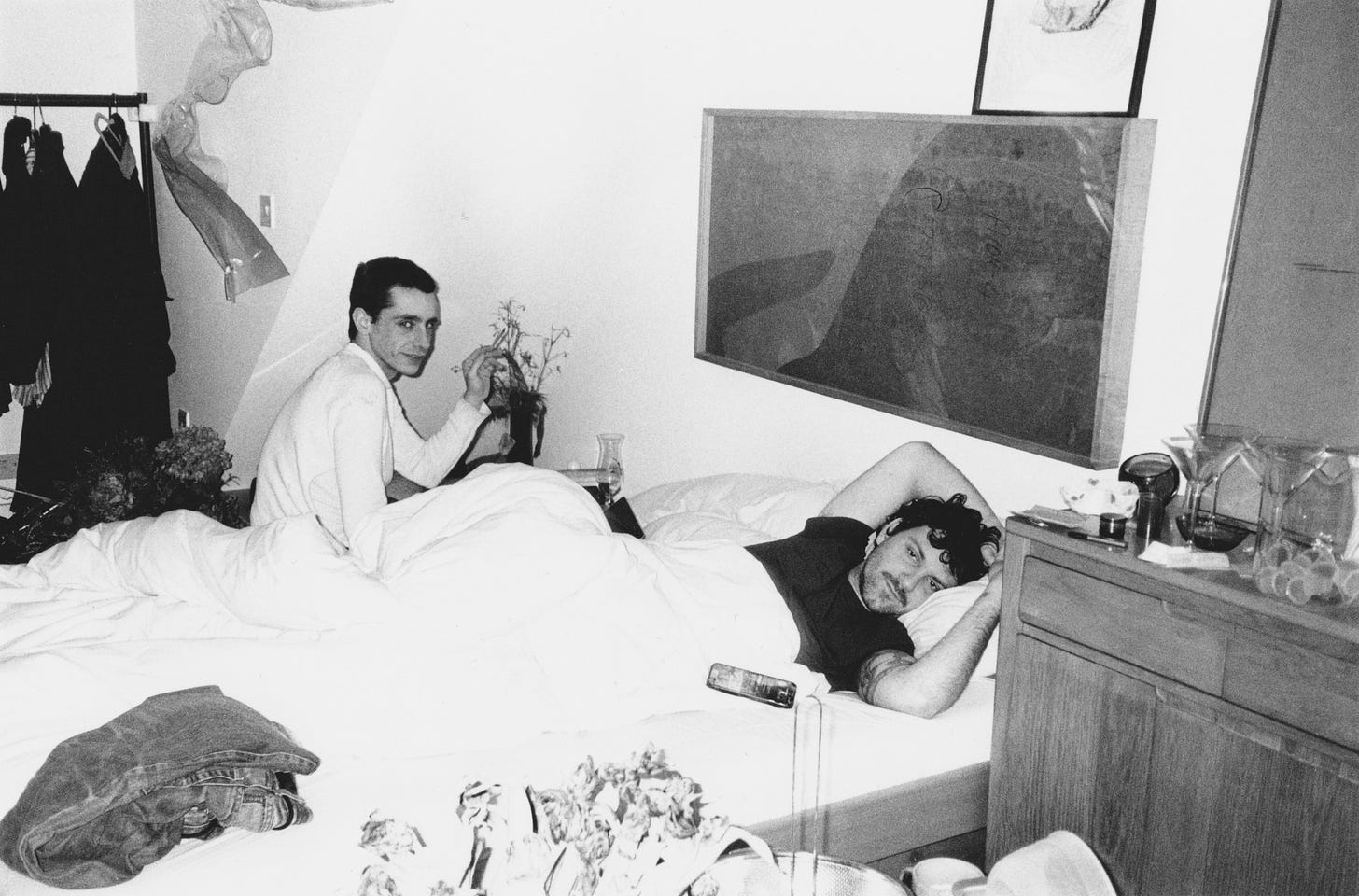

I think the thread that ties the work together is energy. Even though the locations change a lot, hopefully there’s a consistent energy throughout the project. And I think that is what makes the project more a statement for myself, about myself, and what it is that I stand for. Photography is a practice, a verb, something I’m constantly doing. It feels more like a personal diary, a collection of moments, rather than going somewhere with a fixed idea of what to shoot.

Was there an emotional sense of returning to these places that you shot in after you left?

Definitely. Once you find something that truly speaks to you, it creates a sense of belonging. A big part of my practice is about exploring what belonging actually looks like. I left home at a young age, I identify as queer, and live in a country that’s not my own. Navigating all of that has shaped how I understand home and belonging. When you find that feeling of home, no matter where it is, even if it's in the middle of a desert, there’s always a pull to return. Specifically, I’ve been to the Dominican Republic several times because my sister lives there. The work I do there focuses more on documenting the resilience of the queer community, and it’s a collaborative project with them.

I think “A moment opposite to blindness” is more like a more personal, inner search, rather than a documentary about a specific place or community.

Do you mind elaborating a little bit more about the Dominican Republic, and your experience in documenting the queer community?

In every queer community, we often exist in bubbles, and the Dominican Republic is no different. From my outsider perspective, and through conversations with the people I’ve interviewed, the work I’m doing there goes beyond photography, it’s a moving image project. Using video allows me to step back and avoid assumptions. In the conversations I’ve had with people there they talk about how the country has a double morality. It’s one of the few places in the world where abortion is illegal under all circumstances, even in cases of life-threatening situations, abuse, or incest, yet many young people have children as teenagers.

Regarding queerness, there is no government support or representation. The community relies heavily on its own networks. In Santo Domingo, there is a small area with a bar and a cultural center that hosts Kiki balls, serving as important safe spaces. These spaces exist largely outside official support, making life challenging for the community. My project focuses on documenting the ballroom scene there. What’s beautiful is how they’ve made it their own. I’ve been filming with one particular house, Casa Aton, having conversations to understand who they are. Through their life stories and resilience, I hope to share not only their narrative but also a broader story about the island and their determination to thrive.

Since you mentioned ballroom, there was a question that I had about your images. There’s a deep sense of sensual rhythm in your images. How have dance cultures, especially club spaces and industrial music, influenced how you compose, shoot, and feel your way through an image?

Just the other day, I was thinking that I’ve been clubbing for seven years, and I’m like, I need to take a break. Performance in any form has always been really important to me. I was a dancer as a kid, and many of the people I work with are performers too, whether they’re drag artists, contemporary dancers or part of the ballroom scene. There’s something powerful about stepping into a space and creating a collective catharsis with an audience. I’ve experienced that myself when performing, and it’s incredibly healing. That energy, the feeling of shared emotion and release, is something I’m always drawn to in my work. There’s something beautiful in the fact that it’s a shared experience; a connection between queerness and other worlds that I experienced in a nightclub. I remember when I first started going to nightclubs, the feeling of music enveloping you, surrounded by people expressing themselves so iconically, was awe-inspiring. It’s a deeply shared experience.

Though it’s linked to techno and dance music, the act of gathering to dance is ancient and universal. It’s a cathartic, ephemeral ritual that has profoundly shaped who I am and how I process emotions. I’m actually pretty sober, so for me, it’s not about substances, it’s about moving my body for hours, sweating it out, releasing everything, and reconnecting with people. Because I worship these spaces, hopefully that comes through in a way that is consensual, intimate, and sensual rather than exploitative. It’s more like a form of worship. Honestly, I’m not always consciously thinking about it while shooting—it’s just become part of how I see and feel the world.

Do you see image making as a kind of choreography?

You know what? I’m not entirely sure, but probably, yes. I’ve definitely found myself in some really weird physical positions trying to take specific photos, so in that sense, there’s performance happening. There’s a kind of dance happening in looking for something within something that is already happening. I remember making my first art film "Angels that smell of gasoline", and my DOP, Laura Aguilera, was incredible. She was about to shoot a dancer and just said, “You and I are going to dance now.” And that’s exactly what happened, she danced with the camera while he danced with his body. There is something very performative about it.

With this exhibition specifically, I’ve found rhythm and choreography in the sequencing of images. I didn’t want to present isolated photographs; I wanted viewers to enter a kind of universe. Some images are hung really high, some low. Some are static, others full of movement. Some are large, some small. The arrangement becomes a choreography in itself. I was thinking of it like a musical score—a partitura, I think is the word in Spanish. Like sheet music: all these images are the notes, each one meaning something different, and together they create a rhythm you can read or feel as you move through the space. That’s definitely where I see the choreographic element in my work.

It feels like people become part of the show themselves, entering into a dialogue, a choreography, with the work. Too often, looking at art becomes just another thing to check off the day’s list, but it shouldn’t be that way. Art deserves presence and attention.

When I was finishing uni, I actually started photography there, I remember for my degree show I didn’t want to show just images. I wanted to create a light installation. At that time, I was really obsessed with club culture and loved all the lights and atmosphere of clubs. There’s still a part of me that’s curious about creating an experience. One thing I love about performance is that it happens in real time, whereas photography is quite static. Designing a space that feels like an experience was important to me, something that didn’t feel static or overly precious. There are over 50 works included in the show, and I know not every piece will get the same attention, but it’s not about that. It’s about creating a whole environment, using the space for how each person experiences it. It’s about rhythm and hopefully helping viewers find a moment to really grasp something.

The title comes from Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red, which already holds so much longing and mythology. What does that phrase mean to you in the context of this work?

I think there’s something about the feeling I keep chasing in my work, moments of suspended emotion. For me, clubs are full of that suspension, and so is performance: that moment before someone goes on stage, the adrenaline, the tension. It’s like a mix of suspense and violence.

I was rereading Autobiography of Red, and it spoke about the moment when Geryon sees Heracles for the first time. Anne Carson describes it as a moment “opposite to blindness,” which I found brilliant. It speaks about that heartbeat when two people see each other fully. There’s something about that, that we don’t know what truth is. I don’t believe in a fixed definition of truth, but emotional truth feels like that, a deeply embodied experience of “hyper-seeing.” It’s not about the image itself, but about the emotional feeling behind it. That’s the feeling I try to find and keep chasing, so the title felt perfect for this work.

How do you think that mythology, Greek or otherwise, helps us talk about queer love and longing?

That’s a trick question! I mean, I think stories help us understand life. I’ve always been interested in storytelling, especially that ritual of being told a story before bed because it’s soothing and cathartic. You experience something without having to live through it directly, and you learn from it.

When it comes to mythology, I’ve long been obsessed with the idea of angels. I started seeing queer people, especially in club spaces, being fiercely themselves. I’d look around and think, you can’t be from this world. There’s something spiritual about that kind of unapologetic presence. And among all the mythological and religious figures, angels just spoke to me most, and I know that’s not unique to me. A lot of people are really obsessed with angels and have made work about angels. That speaks to a shared imagery that we hold.

I think mythology helps us explore otherness in ways that feel amazing. We’ve all deviated from normative ways in which we could exist, and that’s not even to do with sexuality or queerness. It’s much more broad. It’s that moment you realize you’ve put so much work into knowing who you want to be and getting in touch with your intuition. That is an energy that comes through in a way that feels a bit othered from this world not just from society’s perspective but from a spiritual perspective. So mythology comes through in that I love to tell stories that are kind of impossible We live in a crazy world. You can choose what you want to believe in.

Your work often blurs the line between documentary and dreamscape. How do you decide when to stay close to documentary and when to drift into something dreamier? How do you see photography as a tool for self-identification?

I’m not always fully aware of where the line between documentary and dreamscape falls in my work. It’s something I’ve discovered through the process of making. For me, it comes back to the idea of truth. Life isn’t what we’re taught at school. History is often written by the winners, and those stories can be unfair or incomplete. I remember a project by Walid Raad, who documented the Lebanese Civil War and created The Atlas Group, a series of fictional documents presented with the language of documentary and museum archives. The Atlas Archive was him trying to make sense of what happened during the war by creating imaginary projects. He would choose specific case scenarios and then make projects that acted like documentaries and spoke the emotional truth of what happened. That opened something for me. I realized I didn’t need to work within traditional museums or historical frameworks. I could focus on emotional truth, which can take any form.

So often I lure viewers in through the language of documentary to then speak your truth. The way images are sequenced or paired changes their meaning completely. Photography itself is grounded in real life, but how I associate and frame images, allows me to blur the line between fact and fantasy. I don’t paint or start from a blank canvas, but sometimes it does feel like that when I’m associating images. It’s a bit like playing a game. I think everything we produce becomes a self-portrait. It’s not necessarily about images of yourself. Painters, musicians, and other artists experience something similar. Photography is a discovery tool, a way to process the world. Most of the time, I’m taking photos, then spending time in the darkroom or editing, sitting with my own thoughts and making sense of what I see.

Photography is very much about multitude. It's not about choosing one image that defines you, but about creating a whole world that reflects the complexity of who you are. We’re here to be contradictory and have our emotions and do the best we can do with them.

I view photography as an archive of existence; a brief moment held in time. What kinds of moments are you most drawn to capturing? What do you hope survives in these images? What’s your relationship to the erotic in your work? It feels like you’re showing tenderness more than spectacle.

I don’t wish to make statements. I think a lot of it is a curious self-exploratory way of existing in a world that is deeply fucked up through finding beauty in moments of surrender in a mix of environments. I think there’s a lot of surrendering in the show as a moment of understanding that we will do what we can with what we have, which is not to talk about social justice. It’s more about grieving and sometimes with grief, you have to exercise the letting go part. That is the motivation and intention. I think it’s a universal experience.

How do you know when a moment is intimate enough to hold and not too sacred to keep private?

That is such a good question, because I honestly think right now it’s more important the photos that we don’t take. We live in such a culture of exploitation through images that if something is actually very precious to me, it’s better to not do anything. For me, it’s really about intuition and knowing that consent can be removed at any single point of life. Just because I’ve taken a photo doesn’t mean I have the right to use it. It’s also about the relationship. If there’s real trust, it feels horizontal rather than hierarchical. That intimacy can come through in a way that feels ethical to share.

There was one moment while photographing a ritual space in Mexico where my camera literally broke after I took a shot. It made me question if I should be showing this. I had many conversations with people from the area to really understand what should be shared and what should remain private. One of those images is in the show now and it’s absolutely not for sale. It can be seen, but not owned. That, for me, is another form of respect.

If this exhibition had a smell, a taste, or a song, what would it be?

I think the exhibition would sound like a radio left on in the kitchen while you’re in another room. It’s distant, but still present, soft, maybe even comforting. And then suddenly it plays a song you actually know, and there’s this quiet moment of recognition. It feels slightly remote, but also deeply familiar, like something half-remembered that still reaches you.

What are you dreaming of making next?

I’m still working on the documentary project I mentioned, about the ballroom scene in the Dominican Republic. But one thing that I realized with this show is that I want to shoot broken cars. There’s a feeling of suspension. I feel like if a car was a body, I would be photographing scars. But I’m not always comfortable with the idea of documenting scars on actual bodies; it can easily become exploitative. The ways I was photographing cars I was thinking that we don’t really go through life untouched. There are all these cars that are ruminating, They’re not perfect but are still kind of functioning.